Cumbria has a very long history with sheep. These wooly creatures have been here for thousands of years, and throughout this time they have been of great importance to the people who live here, providing them with a source of food, clothing, jobs, and money.

Sheep were first thought to have arrived in England approximately about 5,000 years ago, when sheep from southwest Asia were brought to Europe, and people began moving from a hunter-gatherer existence to organised farming. It is widely believed that the Vikings brought the ancestors of todays Herdwick sheep into Cumbria when they settled in the area around 900-950 AD. I’m not going to write about the history of the Herdwick here (I’m saving that for another post), but if you visit the fells around Coniston, it is very likely that the sheep you find there will be Herdwicks.

Herdwick sheep have lived on the Cumbrian fells for hundreds of years, where they roam freely in territorial areas called heafs (commonly hefts in the Lakes). The sheep farmers can let their flock roam on the vast unfenced terrain of the fell tops, safe in the knowledge that they won’t simply keep on wandering as they are ‘heafed’ (hefted) to their fell. The female Herdwick adults (yows) teach the heaf (heft) to their lambs, and the same family of sheep will likely have been in that specific area for hundreds of years.

The Herdwick is so hardy that it can even stay on the fell tops during the cold Cumbrian winter. However, in early spring the farmers needed to bring their flocks down from the fell for lambing, and when they did so, they needed to count their sheep.

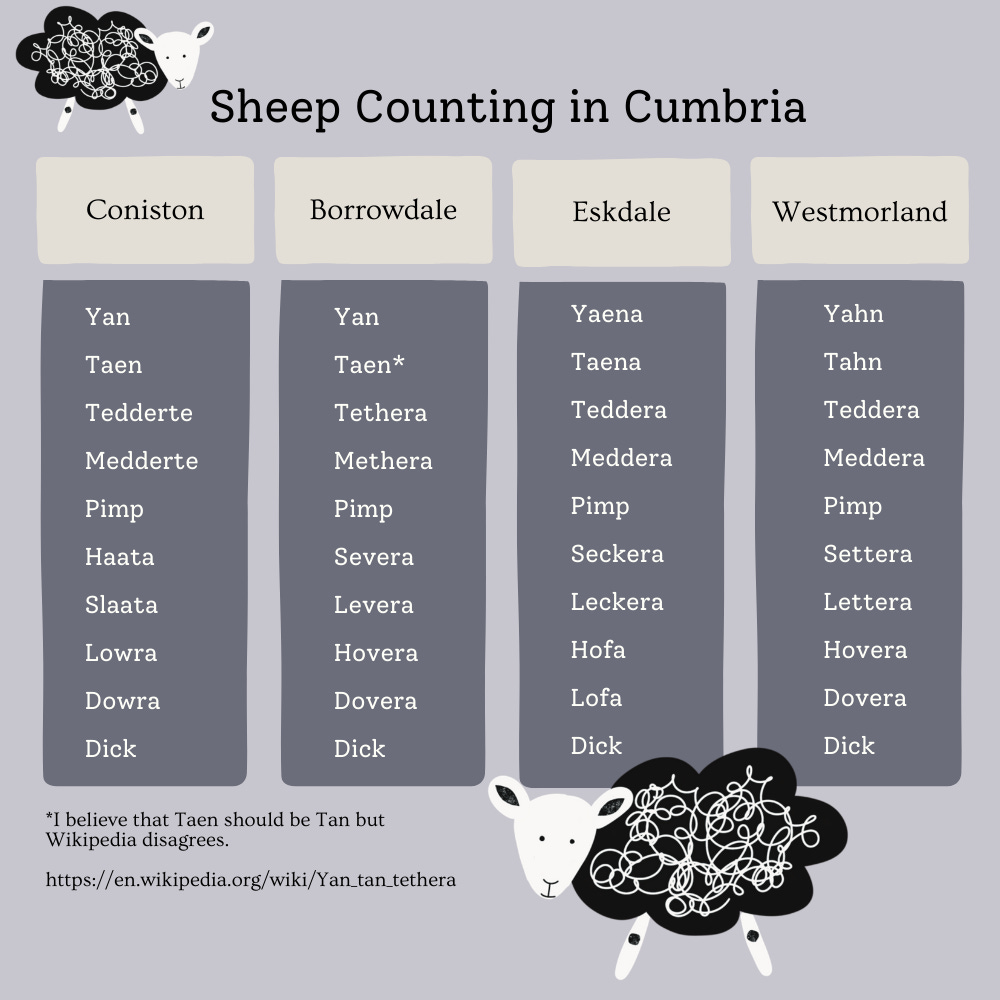

Cumbrian shepherds used to count sheep using a tally system. This involved counting twenty sheep, then transferring a pebble between their pockets, and then at the end of the counting they could count the pebbles to give them the total. That seems sensible enough, but what were the numbers that they used to count to twenty? Given the influence of the Vikings on many place names in Cumbria and in Cumbrian dialect, it would be logical to think that they used Old Norse words for counting. Furthermore, as you can see above, the Old Norse words are somewhat similar to the words we use in English today (and modern Swedish and Norwegian). However, that isn’t the case and the actual words used are totally different, and their origins are complicated.

It seems that sheep counting systems throughout Britain are derived from Brythonic Celtic languages, e.g. Cornish, Cumbric, and modern Welsh. Like the vast majority of Celtic number systems they are vigesimal — meaning that they are based on the number twenty — and they usually don't have words to describe quantities larger than twenty.

The Cumbrian sheep counting numbers are thought to be based upon the extinct Celtic language Cumbric, which was spoken in northern England and the southern Scottish Lowlands during the Early Middle Ages. Unfortunately, there are no known written records of Cumbric. Most of the assumptions about the language come from place names in what is the modern county of Cumbria and the south of Scotland, a handful of dialect words, and (you guessed it) the sheep-counting numbers. From these we can deduce that Cumbric was closely related to Old Welsh. Although, I think given the current use of many Norse words, Cumbric possibly had a heavy Nordic influence, but this is just my opinion.

The Cumbrian sheep counting system is not straight forward as it varied in each valley, as you can see above (and this is by no means all of the variations). If you compare the Cumbrian sheep counting words with those in other parts of the UK, the Cumbrian words have the most in common with the Scots1 words. This is not too surprising as Cumbria and southern Scotland used to be part of Yr Hen Ogledd, ‘the Old North’ in the Early Middle Ages, and then later on in history parts of Cumbria have occasionally belonged to Scotland.

Yan, Tyan, Tethera, Methera, Pimp, Sethera, Lethera, Hovera, Dovera, Dick — Sheep counting words in Scots

Finally, the use of the word yan (or its variations) for one, is a bit of an anomaly in that it doesn’t compare with the Old English, Norse, or Celtic words for one. The vast majority of places in Britain tended to use yan, the major exceptions being Wales (un), Dorset (hant) and Wiltshire (ain).

Interestingly, yan is still regularly used today in Cumbria. Some people think that the use of the word yan for one in Cumbrian, Northumbrian, and some Yorkshire dialects came about because of gradual changes in Northern English. However, there is also the interesting argument that it came from the Jutlandic word for one — jen or jæn.2 (In Nordic languages, j sounds like our y.) With this in mind, it is interesting to note that the Cumbrian and North East dialect word for home — yam (also still commonly in use today) — is similar to the Danish and Jutlandic hjem. It is thought that the majority of Viking settlers in Cumbria were Norwegian, however there is evidence to suggest that at least some of the settlers were of Danish origin,3 therefore it isn’t unreasonable to think that the Cumbrian use of yan came from Jutland Vikings.

Yan aside, it’s very unlikely that you’ll hear anyone in Cumbria using any of the other sheep counting numbers — even the sheep farmers — and they are (somewhat sadly) mainly confined to Cumbrian Folklore. However, the numbers (especially the first three) haven’t been forgotten in the north, and if you say them to most Cumbrians (especially older Cumbrians) they will know what you are talking about.

Footnotes, Further Reading etc…

If you are interested in the Viking history of Cumbria, Paul Eastham regularly writes about the Vikings in his fantastic Substack Hidden Cumbrian Histories.

The Great Mountain Sheep Gather — a beautiful film showing the shepherds bringing their sheep down from their home atop of Scafell Pike — England’s highest mountain at 978 metres (3,209 feet) above sea level.

Thank you for reading about some of the origins of the sheep counting numbers in Cumbria. If you know of any different versions of the words, or if you have ever heard them being used please let me know!

If you enjoyed this please let me know and consider subscribing, sharing or buying me a coffee.

It is important not to confuse Scots, which is a West Germanic language descended from Early Middle English, with the Celtic language Scottish Gaelic. You can read more about Scots here.

Fellows-Jensen G. Scandinavian settlement in Cumbria and Dumfriesshire: the place-name evidence. Baldwin JR, Whyte ID, eds. The Scandinavians in Cumbria. The Scottish Society For Northern Studies:1985;65-82.

I remember singing ’Ca’ the yows tae the knowes’ with my Scottish choir. Your lovely article puts it in perspective!

Thank you Jillian! That's a lovely thing to be able to remember. I think that it's really important that these things are documented and passed down the generations.