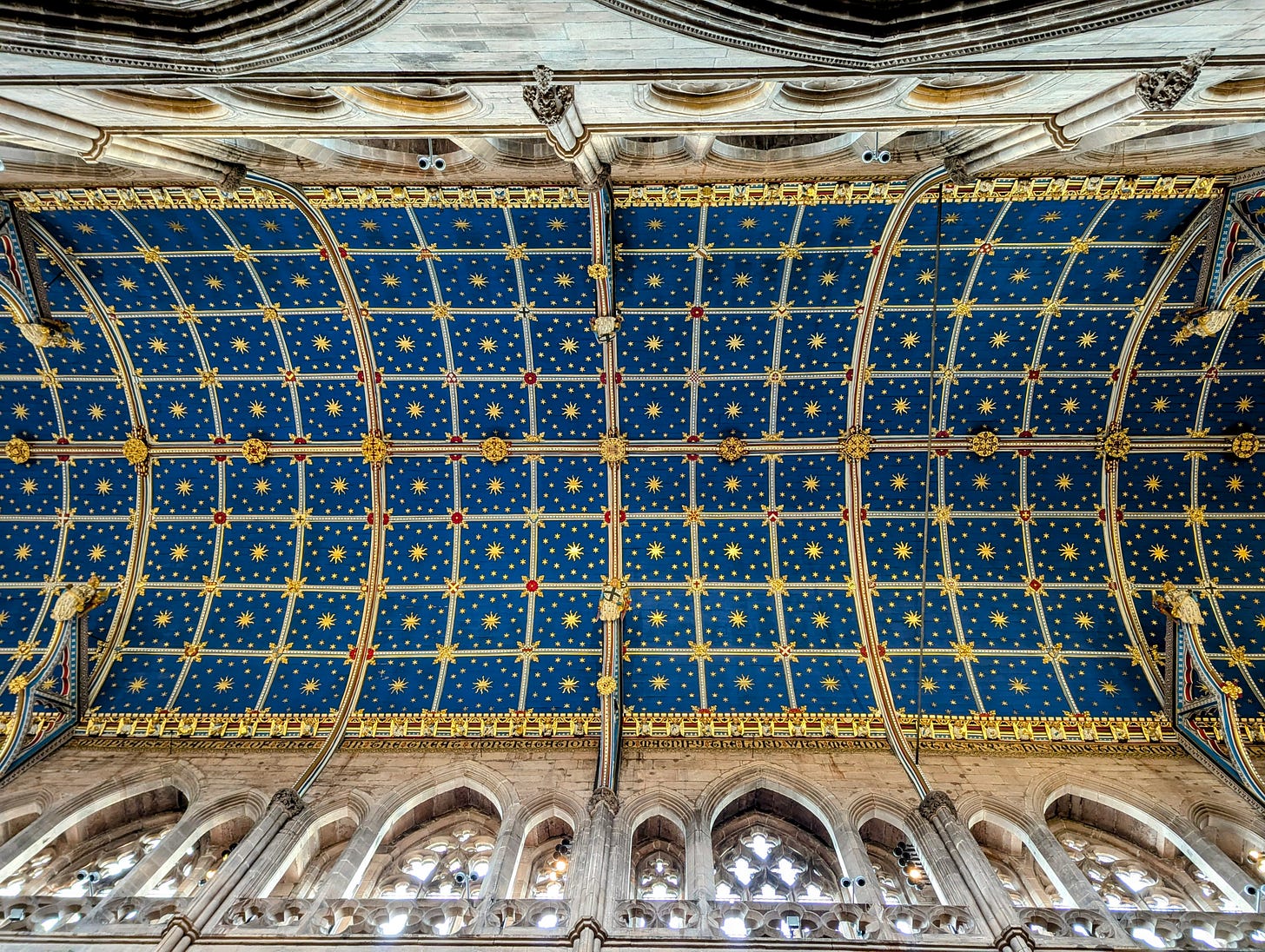

The Starry Heavens of Carlisle Cathedral

A Tiny English Cathedral and its Stunningly Beautiful Ceiling

I’m not a religious person, but I am fond of visiting religious buildings. We are rather spoilt-for-choice in the UK, virtually every town and city (and even some of the tiny villages) has a church or cathedral that contains at least one architectural gem. Carlisle cathedral, in Cumbria, is lucky to have several.

You could write a lot about the long history of this small, but perfectly formed cathedral, but I am not going to. After a quick and extremely concise version, I am going to move onto the ceiling. Given that the cathedral has a documented history of more than 900 years, you may feel that this is a weird thing to focus on, but it is so beautiful, that if you ever visit,1 you will understand why.

What is now Carlisle cathedral was founded as an Augustinian priory in 1122, during the reign of King Henry I. It became a cathedral in 1133, when Henry I appointed his former confessor Æthelwold to be in charge of the newly founded Diocese of Carlisle.2 The cathedral that stands today is a mixture of architecture dating from Norman times, the 14th century, and the extensive renovation that took place in the 1800s. Sadly, most of the Norman parts of the cathedral, along with a lot of the brand new Gothic choir were badly damaged by fire in 1292. The fire, which destroyed and damaged many buildings, was started elsewhere in Carlisle by a young man called Simon of Orton, who was a little bit angry to discover that he had been left out of an inheritance. On learning the news, he seemingly decided that burning huge swathes of Carlisle (or Carleol as it was known then) to the ground would be a reasonable way of venting his frustrations.

Whilst it is one of England’s smallest cathedrals (and one of only four Augustinian churches in England to become a cathedral), there is plenty to see. The east window of the cathedral is often cited as its true architectural jewel. The window, which dates from 1350, is the largest and most complex window in the flowing decorated gothic style in England. Quite amazingly, the glass in the upper section of the window is still the original medieval3 glass. The glass in the nine lower sections of the window dates from a much more modest 1861. There is a theory that the height of the top sections of the window saved the medieval glass from stone throwing protestants during the Reformation, however there is no strong evidence to support this theory. I wish I had taken a better picture of the window as it truly is beautiful, the problem I have is that I get totally distracted by the ceiling whenever I visit, so I don’t have many pictures of anything else.

The main roof timbers of the barrel-vaulted choir and sanctuary ceiling date from 1400. Whereas the beautiful mid-blue sky and gold stars date from a major restoration of the cathedral that took place during 1853 and 1856. The style follows that of the original medieval ceiling, but the angels, stars and colour choices were the work of the renowned British Architect Owen Jones (1809-1874), whose work often featured bold colours, and was heavily inspired by Islamic art.4 The ceiling has an intricate geometric design, with each blue panel containing sixteen golden stars and a central aureate sun (well I think it’s a sun). There is, apparently, one panel that contains only 15 stars, but I have never spotted it so far. If you sit and take a closer look at the ceiling you will see a face gazing down at you from a roof boss. It is alleged that this is the face of St Mary, whom the cathedral is dedicated to. I’d just like to add that if you are thinking that the ceiling looks to be in tip-top shape for something painted in the 1850s, you are rightly curious — the ceiling was repainted in 1970.

Form without colour is like a body without a soul. Owen JonesAs I mentioned above, in addition to the ceiling and the east window, the cathedral has several other interesting features. These include Viking runic inscriptions, and medieval painted panels and carvings. If you are ever passing near Carlisle, I would highly recommend visiting the city. It has a long and fascinating history, and as well as the cathedral, I recommend a visit to the castle (where Mary Queen of Scots was imprisoned) and Tullie House (which houses an impressive collection of Roman finds from the city, and has regular well-curated art exhibitions).

I’ve not been able to find a mention of the cathedral on any “most beautiful ceilings in the…,” list, however I really think it deserves a mention. If you’d like to learn about some more cathedral ceilings in England5 there is a lovely article by the Association of English Cathedrals — and Carlisle does make an appearance this time.

Thank you for reading. If you enjoyed this please let me know and consider subscribing, sharing or buying me a coffee.

If you don’t know where Carlisle is, it is a small city in the very north of England, and is part of the county of Cumbria. Situated just 8 miles from the current Scottish border, Carlisle has a long and turbulent history, and has been part of Scotland several times. You can find out more about the cathedral here.

Henry I set up the Diocese of Carlisle to try and establish his authority in this rather unruly part of the country. By this point in history, Carlisle had been part of Scotland before, there was a heavy Celtic influence in the area, and the locals had a tendency to look towards Glasgow for spiritual guidance. I would like to add that Henry’s strategy of creating the diocese to stabilise the area failed miserably, and in late 1135 David I, King of Scotland, invaded and took control of the area—which then remained under Scottish control until 1157 when Henry II reclaimed it (for a while).

I still feel wrong typing medieval and not mediaeval (I am probably well and truly revealing that I am no longer in my 20s here), but medieval is now the Oxford English Dictionary’s preferred spelling.

Owen Jones was one of the most influential design theorists of the 19th century. His theories on the use of colour, geometry and abstraction, which were heavily influenced by his travels in Italy, Greece, Egypt and Turkey, were the basis of his design sourcebook The Grammar of Ornament, which is still in print today, nearly 170 years after its publication. The V&A website has an interesting read entitled Owen Jones and the Grammar of Ornament.

A good example of sentences that you think you will never write.

A wonderful work of artistry and craftsmanship. I shall definitely make a point of visiting if ever I’m in the area. I recently walked round Winchester Cathedral obsessed by the floor, so I like the fact that you honed in on the ceiling!